When you buy through our links, we may earn a commission. Products or services may be offered by an affiliated entity. Learn more.

Sleep Deprivation

- Symptoms: Sleep deprivation symptoms include daytime tiredness, slowed reaction times, trouble focusing, impaired mental or physical performance, and mood changes.

- Causes: It can be caused by not getting enough sleep due to work, school, or social activities or factors that contribute to broken sleep, like noise or obstructive sleep apnea.

- Effects: It can lead to poor performance at work or school, an increased risk of car crashes and other accidents, and an elevated risk of health problems, including high blood pressure, depression, stroke, and death.

- Treatment and Prevention: Restoring the amount of sleep a person gets (between 7 and 9 hours for most people) is imperative. This can be done by practicing good sleep hygiene and addressing factors that cause disrupted sleep.

Millions of adults aren’t getting the sleep they need. Around 1 in 5 U.S. adults sleep less than five hours a night, far below the recommended seven to nine hours. Chronic sleep deprivation is a condition that can take a serious toll on your physical and mental health, often without you realizing it. In this article, we’ll explore the symptoms of sleep deprivation, how it’s diagnosed, and practical ways to prevent and treat it.

Overview of Sleep Deprivation

Sleep deprivation, also known as insufficient sleep, describes repeatedly not getting as much sleep as you need. People often become sleep-deprived because of their work commitments, social life, personal habits, or factors that disrupt sleep. This leads to a lack of alertness during the day, and over time, it also poses many mental and physical health risks.

Stages of Sleep Deprivation

When people talk about stages of sleep deprivation, they’re referring to what happens when you go without any sleep at all. While there are no universally agreed-upon stages of sleep deprivation, studies have found the following effects tend to occur after a person stays awake for a certain number of hours.

- 24 hours without sleep: After being awake for a full 24 hours, a person may become anxious and irritable, feel unlike themselves, act disoriented, and begin noticing minor distortions in how things look, sound, or feel.

- 48 hours without sleep: Going two days without sleep might result in existing symptoms becoming more severe and complex hallucinations developing. These hallucinations could include seeing or hearing things that aren’t there.

- 72 hours without sleep: At this stage, a person is likely to experience extreme sleep deprivation symptoms that resemble psychosis. They may see, hear, and feel things that aren’t present, believe things that aren’t true, and have unusual or intense emotions and behaviors that don’t correspond with reality.

Although the symptoms of total sleep deprivation can be severe, they usually resolve after a person gets sleep again.

Sleep Deprivation vs. Insomnia

Sometimes people confuse sleep deprivation with insomnia, since both involve obtaining less sleep than a person needs to be healthy and alert. These two conditions are different, however. With sleep deprivation, a person can easily fall asleep and stay asleep, but their schedule doesn’t allow for adequate sleep or for some other reason they choose not to get the quality sleep they need.

With insomnia, a person has ample opportunity to sleep, but they struggle with falling asleep, staying asleep, or both.

Struggling to Stay Awake? Take an At-Home Sleep Test

our partner at sleepdoctor.com

10% off Home Sleep Tests

Buy Now“Truly grateful for this home sleep test. Fair pricing and improved my sleep!”

Dawn G. – Verified Tester

Sleep Deprivation Symptoms

Sleep deprivation can lead to many symptoms, including:

- Daytime tiredness

- Slower reaction time

- Trouble paying attention

- Brief daytime sleep periods, also known as microsleeps

- Unplanned naps

- Difficulty thinking and being logical

- Mood changes, including irritability

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Reduced interest in sex

- Lower quality of life

- Reduced social activity due to tiredness

When a person experiences sleep deprivation, they may sleep longer on their days off work or days without social plans. If a person sleeps much longer than usual on weekends or vacations, that could be a sign they aren’t getting enough sleep on regular nights.

Causes of Sleep Deprivation

Sleep deprivation can be caused by poor sleep habits, including inconsistent sleep schedules, long daytime naps, the use of digital devices before bed, or a noisy or bright sleep environment. Consuming substances like caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine may also lead to obtaining less sleep than is necessary for daytime alertness.

A person’s work schedule or social obligations can also contribute to sleep deprivation. For example, if a person works full-time, has a daily commute, and also has to take care of children each evening, there might not be enough time left for them to sleep as much as they need at night.

Sleep disorders and prescription medications can also cause a person to fall short on sleep. For example, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is often mentioned in relation to sleep deprivation, because, when untreated, it can cause a person to briefly wake up dozens of times each hour, leading to fragmented sleep. These brief awakenings also disrupt the sleep cycle, potentially keeping a person from getting enough of certain types of restorative sleep, like deep sleep.

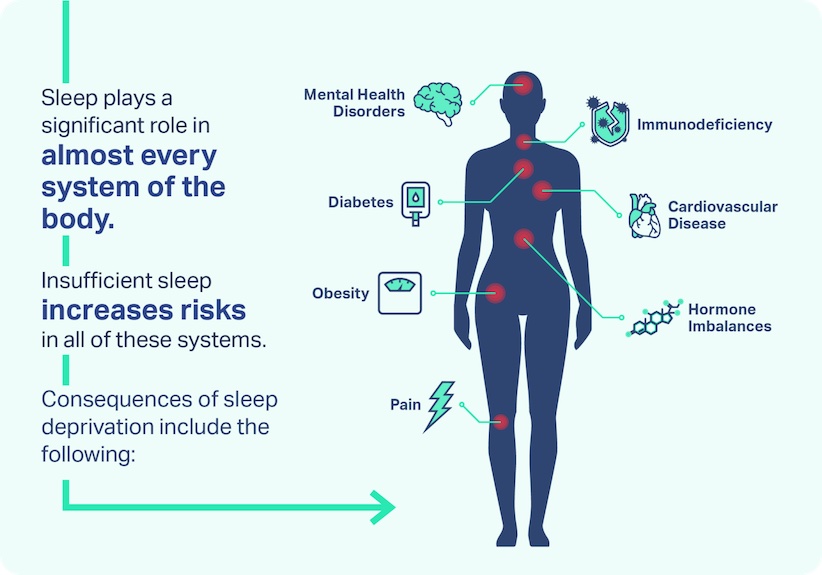

Effects of Sleep Deprivation

Potential effects of sleep deprivation can become severe, especially if the deprivation continues over an extended period of time. Sleep deprivation has been linked to:

- High blood pressure

- Type 2 diabetes

- Obesity and metabolic syndrome

- Kidney disease

- Increased inflammation and an altered immune system

- Heart disease and stroke

- Higher cholesterol

- Higher risk of death from any cause

- Higher risk of car crashes and serious injuries

- Anxiety, depression, and emotional instability

- Irritability and aggression

- Impaired attention span

- Relationship conflicts

- Poor judgment and decision-making

- Trouble reading people’s emotions

Diagnosing Sleep Deprivation

Sleep deprivation is generally only diagnosed after it’s become severe and chronic, which is usually after a person has fallen short on sleep for most nights over three or more months. At this point, sleep deprivation is referred to as insufficient sleep syndrome (ISS) or chronic sleep deprivation (CSD).

Doctors diagnose insufficient sleep syndrome when a person:

- Falls asleep or becomes extremely tired during the day

- Sleeps less than recommended for their age group

- Sleeps less than recommended most nights for at least three months

- Wakes up due to an alarm or another person most days and would sleep longer if it were possible, such as on vacations or days off work

- Feels less tired during the day after getting more sleep

- Knows their symptoms aren’t caused by a sleep disorder, a physical or mental health problem, or drug use or withdrawal

To determine if someone is experiencing sleep deprivation, a doctor typically starts by reviewing their sleep history. They may ask questions about sleep and wake times, work schedules, sleep quality, daytime naps, and feelings of fatigue.

People being evaluated for sleep deprivation may be asked to keep a sleep diary or wear an actigraphy device, which is a watch-like tool that tracks movement to provide insight into sleep patterns.

Doctors may also ask about additional symptoms to rule out another sleep disorder or medical condition. If another issue is suspected, further testing such as a sleep study may be recommended.

Sleep Deprivation Treatment and Prevention

The best way to treat and prevent sleep deprivation is to get enough sleep. Experts recommend that adults sleep for between seven and nine hours each night. The ideal amount of sleep varies from person-to-person, and you can identify how much sleep you need by seeing how much you naturally sleep when you aren’t woken up by an alarm or another person.

Here are tips for getting adequate sleep:

- Go to sleep and wake up at the same time every day.

- Follow a calming bedtime routine every night in the hour or two before bed.

- Avoid using digital devices before bed and during any nighttime awakenings.

- Only take daytime naps that are shorter than 30 minutes.

- Engage in physical activity every day for at least 20 minutes.

- Keep the bedroom dark, cool, and quiet.

- Choose a mattress, bedding, and pillows you find comfortable.

- Avoid caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine in the evening.

When to See a Doctor

If you feel tired during the day or believe you may be experiencing symptoms stemming from sleep deprivation, experts recommend seeing a doctor. Your doctor can help you determine what might be causing your short sleep, daytime tiredness, and any other symptoms. Seeing a doctor early on may also help prevent a car crash or other accident, as well as prevent an increased risk for a variety of mental and physical health issues.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you die from sleep deprivation?

While it’s uncommon for people to die directly from a lack of sleep, long-term sleep deprivation can contribute to a range of health problems that may become life-threatening. Sleep deprivation also increases the risk of serious car crashes, falls, and workplace accidents due to the associated cognitive impairments.

Does sleep deprivation cause high blood pressure?

Chronic sleep deprivation has been linked to high blood pressure, and some experts suspect there’s a cause-and-effect relationship between the two factors. There’s also some evidence suggesting that going one night without sleep can increase blood pressure, as well.

Can sleep deprivation cause headaches?

Headaches are not usually named as a common effect of chronic sleep deprivation. However, some studies have found that sleep deprivation can trigger migraines and tension headaches among people who get them. Sleep deprivation has been found to temporarily help prevent cluster headaches, however.

Can sleep deprivation cause brain damage?

It may, especially if sleep deprivation is severe or chronic. Animal studies suggest that prolonged or repeated sleep deprivation can cause structural and potentially irreversible damage in critical brain regions.

However, researchers are still figuring out exactly what impact it has in humans and how that impact occurs. Whether or not sleep deprivation definitively causes brain damage isn’t yet known, but it’s clear that the brain benefits from adequate sleep.

Still have questions? Ask our community!

Join our Sleep Care Community — a trusted hub of sleep health professionals, product specialists, and people just like you. Whether you need expert sleep advice for your insomnia or you’re searching for the perfect mattress, we’ve got you covered. Get personalized guidance from the experts who know sleep best.

References

14 Sources

-

Fioroni, S., & Foy, D. (2024, April 15). Americans sleeping less, more stressed. Gallup Inc.

https://news.gallup.com/poll/642704/americans-sleeping-less-stressed.aspx -

Schwab, R. J. (2020, May). Insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS). Merck Manual Consumer Version.

https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/brain,-spinal-cord,-and-nerve-disorders/sleep-disorders/insomnia-and-excessive-daytime-sleepiness-eds -

Shah AS, Pant MR, Bommasamudram T, et al. Effects of Sleep Deprivation on Physical and Mental Health Outcomes: An Umbrella Review. Am J Lifestyle Med. Published online May 27, 2025. doi:10.1177/15598276251346752

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40443808/ -

Waters, F., Chiu, V., Atkinson, A., & Blom J. D. (2018). Severe sleep deprivation causes hallucinations and a gradual progression toward psychosis with increasing time awake. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 303.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30042701/ -

Maski, C. (February 2024). Insufficient sleep: Evaluation and Management. In T. Scammell & A. Eichler (Ed.). UpToDate.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/insufficient-sleep-evaluation-and-management -

Cirelli, C. (2024, May). Insufficient sleep: Definition, epidemiology, and adverse outcomes. In R. Benca & A. Eichler (Ed.). UpToDate.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/insufficient-sleep-definition-epidemiology-and-adverse-outcomes -

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). What are sleep deprivation and deficiency?

https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/sleep-deprivation -

Al-Rashed F, Alsaeed H, Akhter N, Alabduljader H, Al-Mulla F, Ahmad R. Impact of sleep deprivation on monocyte subclasses and function. The Journal of Immunology. Published online February 24, 2025. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jimmun/vkae016

https://academic.oup.com/jimmunol/article/214/3/347/8037869 -

Mader EC Jr, Mader ACL, Singh P. Insufficient Sleep Syndrome: A Blind Spot in Our Vision of Healthy Sleep. Cureus. 2022;14(10):e30928. Published 2022 Oct 31. doi:10.7759/cureus.30928

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36337802/ -

Consensus Conference Panel, Watson, N. F., Badr, M. S., Belenky, G., Bliwise, D. L., Buxton, O. M., Buysse, D., Dinges, D. F., Gangwisch, J., Grandner, M. A., Kushida, C., Malhotra, R. K., Martin, J. L., Patel, S. R., Quan, S. F., Tasali, E., Non-Participating Observers, Twery, M., Croft, J. B., Maher, E., … Heald, J. L. (2015). Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: A joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 11(6), 591–592.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25979105/ -

Sá Gomes E Farias AV, de Lima Cavalcanti MP, de Passos Junior MA, Vechio Koike BD. The association between sleep deprivation and arterial pressure variations: a systematic literature review. Sleep Med X. 2022;4:100042. Published 2022 Jan 26. doi:10.1016/j.sleepx.2022.100042

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35169694/ -

Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C., Fernández-Muñoz, J. J., Palacios-Ceña, M., Parás-Bravo, P., Cigarán-Méndez, M., & Navarro-Pardo, E. (2017). Sleep disturbances in tension-type headache and migraine. Therapeutic advances in neurological disorders.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29399051/ -

Alkadhi K, Zagaar M, Alhaider I, Salim S, Aleisa A. Neurobiological consequences of sleep deprivation. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2013;11(3):231-249. doi:10.2174/1570159X11311030001

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3648777/ -

Zhou Y, Li H, Liu X, et al. The Combination of Quantitative Proteomics and Systems Genetics Analysis Reveals that PTN Is Associated with Sleep-Loss-Induced Cognitive Impairment. J Proteome Res. 2023;22(9):2936-2949. doi:10.1021/acs.jproteome.3c00269

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37611228/