When you buy through our links, we may earn a commission. Products or services may be offered by an affiliated entity. Learn more.

Circadian Rhythm

- What Is Circadian Rhythm?

- How Do Circadian Rhythms Work?

- What Can Disrupt Your Circadian Rhythm?

- What Happens if Your Circadian Rhythm Is Off?

- How Do You Maintain a Healthy Circadian Rhythm?

- How Do You Fix Your Circadian Rhythm?

- What Are Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders?

- When Should You See a Doctor?

- Circadian rhythms are 24-hour cycles that help govern essential bodily functions—especially the sleep-wake cycle—by syncing internal processes with the day–night cycle.

- Disruptions from factors like irregular schedules, travel, shift work, screen time, or underlying health issues can throw off your internal clock and negatively impact sleep and overall well-being.

- Maintaining a consistent sleep schedule and daily routine, along with strategies like timed light exposure and melatonin supplementation when needed, are the most effective ways to support a healthy circadian rhythm.

Have you ever wondered why taking a nap seems particularly appealing in the middle of the afternoon, why jet lag hits you harder when you travel eastward, or why your ideal bedtime is so different from your partner’s? The answers to all of these questions involve circadian rhythms, the natural patterns that take place in your body over the course of each 24-hour cycle.

Circadian rhythms affect many bodily processes, your mental state, and your behavior. Perhaps the most well-known circadian rhythm is the sleep-wake cycle, which determines how sleepy or alert you feel throughout the day and night. We cover how circadian rhythms work, particularly in connection with sleep, along with how to prevent and address disruptions to your circadian rhythms.

What Is Circadian Rhythm?

Through millions of years, life has been shaped by the world’s rhythmic shifts of night and day. Many living things—including plants, animals, and humans—have circadian rhythms, which are tailored to life on earth and the changes that occur as the planet rotates on its axis.

Every 24 hours, predictable shifts in light and temperature take place. Circadian rhythms help living things respond to changes in their environment in ways that conserve energy, help them find food, and allow them to grow and heal.

In humans, circadian rhythms serve many functions, including helping regulate :

- Sleeping and waking

- Core body temperature

- The immune system

- Hormones

- Metabolism

- Cognitive function

- The body’s reaction to stress

Sleep and Circadian Rhythm

Circadian rhythms play a vital role in a person’s ability to sleep in one consolidated block of time at night and to stay up for roughly 16 hours straight every day. As the sun sets in the evening, the brain begins producing melatonin, a hormone that induces sleepiness. Core body temperature also drops, contributing to decreased alertness.

These changes, driven by circadian rhythms, combine with sleep drive to cause a person to fall asleep at night. In the morning, as exposure to light increases, melatonin production stops and body temperature rises, promoting wakefulness.

Sleep is most likely to be refreshing and restorative when circadian rhythms, the natural cycle of daylight and darkness, and sleep patterns align.

How Do Circadian Rhythms Work?

Circadian rhythms are controlled by biological clocks located in organs and glands throughout the body, but all of these peripheral clocks are commanded by a “master clock” in a region of the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN).

In most adults and adolescents, this master clock operates on a cycle that’s slightly longer than 24 hours. In order to maintain alignment with the 24-hour rotation of the planet, the master clock must adjust by about 12 to 18 minutes every day. For this reason, it times circadian rhythms according to environmental cues known as “zeitgebers,” German for “timekeepers.”

Light and darkness are the most important and powerful zeitgebers. Other zeitgebers involved in circadian timing include :

- Meals

- Exercise

- Social interactions

- Daily routines

- Stress

These zeitgebers trigger the release of hormones in the brain and the delivery of chemical signals to body tissues. Thus, the master clock is able to effectively time vital body functions, such as the conversion of food into energy, fluctuations in body temperature, and when a person feels like sleeping or waking up.

Babies, Toddlers, and Children

Circadian rhythms begin developing shortly after birth, but newborns don’t have a fully established internal clock, which is why their sleep can seem unpredictable. Around 2 to 4 months of age, babies start to sync with the natural light-dark cycle, gradually developing more regular sleep and feeding patterns. By toddlerhood and early childhood, most kids follow a more predictable circadian rhythm, often rising early and needing naps or early bedtimes to meet their sleep needs.

Teenagers

During puberty, circadian rhythms shift later—a phenomenon known as a “sleep phase delay.” This biological change causes teens to feel sleepy later at night and want to wake up later in the morning. Unfortunately, early school start times often conflict with this natural rhythm, contributing to sleep deprivation and difficulty concentrating during the day.

Adults

In adulthood, circadian rhythms tend to stabilize around a more traditional pattern of feeling sleepy at night and alert during the day. However, individual preferences still vary. Some people are naturally early risers (“morning larks”), while others are night owls. Work demands, stress, and lifestyle factors can all influence how closely an adult’s sleep habits align with their internal clock.

What Can Disrupt Your Circadian Rhythm?

Your circadian rhythm is your body’s internal clock, helping regulate sleep, wakefulness, hormone release, and other biological processes over a 24-hour cycle. But this rhythm can be thrown off by a variety of internal and external factors. Common disruptors include:

- Irregular sleep schedules: Staying up late, sleeping in on weekends, or frequently changing your bedtime can confuse your body clock and make it harder to fall asleep or wake up consistently.

- Shift work or jet lag: Working night shifts or traveling across time zones disrupts your natural light-dark exposure, which can shift your internal clock out of sync with your environment.

- Too much screen time at night: Blue light from phones, tablets, and computers can suppress melatonin production—a hormone that helps you sleep—and delay your natural sleep-wake cycle.

- Exposure to artificial light at night or lack of natural light during the day: Bright indoor lighting at night and insufficient sunlight during the day can confuse your brain’s understanding of when it’s time to be awake versus asleep.

- Underlying health conditions or medications: Conditions like depression, insomnia, or neurological disorders, as well as certain medications, can interfere with your circadian rhythm and sleep quality.

- Poor sleep environment or habits: Inconsistent bedtime routines, high stress, caffeine or alcohol use before bed, and an uncomfortable sleep space can all interfere with your body’s natural rhythm.

What Happens if Your Circadian Rhythm Is Off?

If you don’t sleep when your body tells you that it’s time to—or if you sleep for long periods during the day—your circadian rhythms might become misaligned with the 24-hour cycle of day and night.

Misalignment between your circadian rhythms and your environment, especially over the long term, can have serious consequences for your health and wellbeing. These include:

- Sleep problems: Misaligned circadian rhythms can make it harder to fall asleep at bedtime, lead to more wake-ups during the night, and result in less sleep overall. Misalignment can first be confused as insomnia but frequent misalignment can in fact contribute to the development of insomnia.

- Performance issues: If your circadian rhythms are off, you’re likely to experience a range of issues that affect your ability to function, such as excessive sleepiness, difficulty focusing, memory problems, and difficulty performing high-precision tasks.

- Emotional and social difficulties:Sleep deprivation makes it harder to manage stress and to regulate emotions, so if your circadian rhythms are out of sync, you’re more likely to experience mental health struggles like depression and conflict in your relationships.

- Accidents and errors: Misaligned circadian rhythms increase your risk of having a car accident, making a serious mistake at work, or getting hurt on the job.

- Health problems: A range of health problems are associated with out-of-sync circadian rhythms, including obesity, diabetes, heart attacks, high blood pressure, and cancer.

- Fatigue: Chronic misalignment of circadian rhythms or a lack of a routine to help entrain the internal clock can cause symptoms of low energy and grogginess.

How Do You Maintain a Healthy Circadian Rhythm?

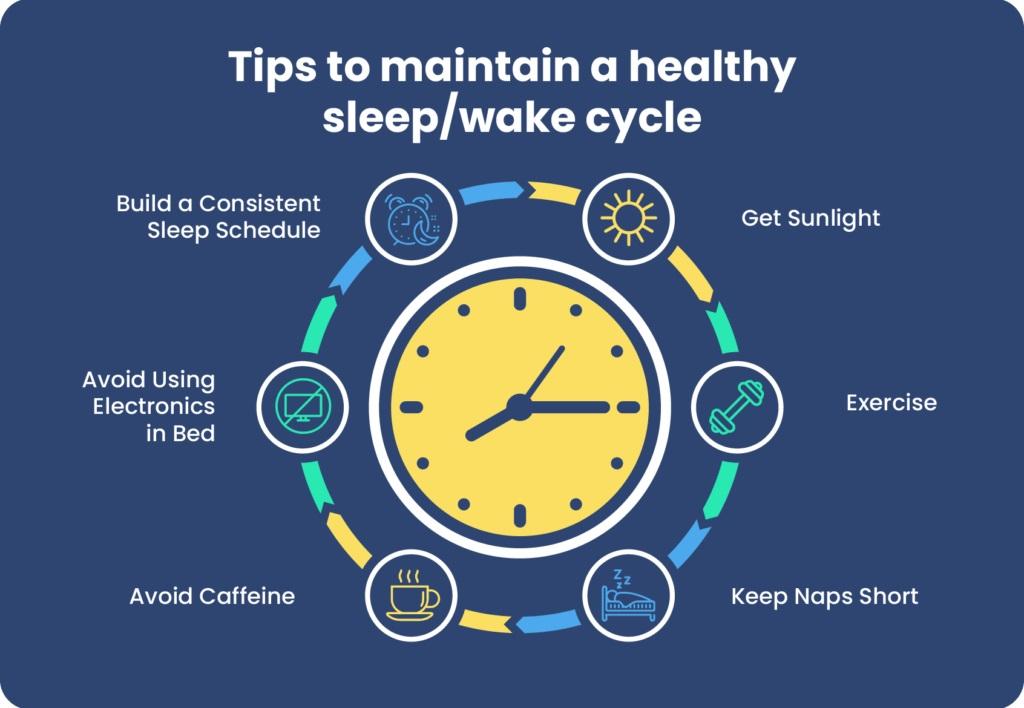

Following sleep hygiene guidelines can help ensure that your sleep-wake cycle aligns with your circadian rhythms.

- Maintain a regular schedule: To the extent that it’s possible, eat your meals, go to bed, and wake up at the same time every day.

- Implement a bedtime routine: Choose one to three relaxing activities, like taking a warm bath or stretching, and do them before bed every night.

- Exercise: Get regular physical activity during the daytime.

- Avoid naps late in the day: Naps, especially in the late afternoon, can interfere with your ability to fall asleep at bedtime.

- Avoid screens and bright light before bed: Light, particularly blue light produced by electronic devices, can inhibit melatonin production, so it’s important to avoid light exposure when you’re trying to wind down.

- Enjoy sunlight during the day: In the morning, open the curtains, and if you feel tired during the day, spend a few moments outside.

If you’re a shift worker or you have travel plans, talk to your doctor about how to minimize misalignments between your circadian rhythms, your sleep schedule, and your environment.

How Do You Fix Your Circadian Rhythm?

Many people experience disruptions to their circadian rhythms at some point in their lives. If your circadian rhythms are out of sync with your environment, there are several approaches that might help you bring them back into alignment.

- Light therapy: This common treatment for disrupted circadian rhythms involves strategically timed exposure to light and darkness. Controlling exposure to light can alter melatonin production and shift sleep and wake times earlier or later. This is often accomplished through the use of a light box or light-blocking glasses.

- Melatonin supplements: In some circumstances, melatonin supplements are an effective way to induce sleepiness at appropriate or desired times. Correct timing and dose of melatonin is important to help adjust the circadian rhythm effectively. This strategy can help travelers advance their bedtimes and may help individuals with certain circadian rhythm disorders adjust their sleep schedules.

- Sleep schedule adjustments: Strategic adjustments to your sleep schedule may help realign your circadian rhythms. If you’re a shift worker, implementing a consistent sleep schedule, even on your off days, may help. If you’re a frequent traveler, gradually adjusting your sleep schedule in small increments can help you minimize the effects of jet lag.

- Medications: In some cases, your doctor might recommend using medications to induce sleep or promote wakefulness. However, these medications can pose risks and may have undesirable side-effects, so they’re often a second-line treatment for disrupted circadian rhythms and circadian rhythm sleep disorders.

Before beginning any therapy intended to realign your circadian rhythms, make sure to talk to your doctor about your symptoms and treatment plans.

What Are Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders?

There are six sleep disorders that can cause abnormalities in a person’s ability to sleep and wake in expected 24-hour patterns. Some of these disorders are environmental in nature or “extrinsic,” meaning that they happen when a person’s activities or circumstances cause their circadian rhythms to desynchronize from their environment. Other disorders are “intrinsic”—that is, they happen when a person’s circadian timekeeping system doesn’t function properly.

- Shift work disorder: This disorder occurs when shift work prevents a person from sleeping according to their natural circadian rhythms. People with this disorder often struggle to stay awake during night shifts and to sleep at home during the day, which results in sleep deprivation. There’s further disruption as many shift workers change sleep schedules throughout the week depending on if they’re working or not working.

- Jet lag disorder: When people travel across multiple time zones, their circadian rhythms won’t initially align with the light-dark cycle in their new environment. This can result in jet lag, which causes daytime sleepiness, digestive problems, and sleep difficulties.

- Advanced sleep-wake phase disorder: Individuals with this disorder feel sleepy before their desired bedtime and wake up very early in the morning. Sleep debt occurs when people with this disorder force themselves to stay up late, as they’re unable to sleep in.

- Delayed sleep-wake phase disorder: People with this disorder don’t feel ready for bed until very late at night, and they struggle to get up at conventional wake times. They would sometimes feel a “second wind” in the evening and this pattern is frequently labeled as being a “night owl”. This can result in sleep loss for people with work, school, or family obligations in the morning.

- Non-24-hour sleep-wake rhythm disorder: In people with this disorder, the master clock driving circadian rhythms fails to make the daily corrections that align it with the 24-hour day. Their internal clock may shift by a few minutes or hours every day, making it difficult to maintain a routine and sleep at night or stay awake during the daytime.

- Irregular sleep-wake rhythm disorder: For individuals with this disorder, sleeping and waking are not governed by circadian rhythms. As a result, sleep tends to happen in short intervals interspersed throughout the day without a clear pattern.

When Should You See a Doctor?

While occasional disruptions to your sleep-wake cycle are normal, persistent issues may be a sign of a circadian rhythm sleep disorder. You should consider seeing a doctor if:

- You regularly struggle to fall asleep or stay asleep despite keeping a consistent schedule.

- You feel excessively sleepy during the day, even after a full night’s rest.

- Your sleep-wake times are significantly delayed or advanced compared to most people (e.g., you’re only able to fall asleep in the early morning hours).

- Your job or lifestyle requires frequent shifts in your sleep pattern, and it’s affecting your health or functioning.

- You suspect your sleep issues are impacting your mood, memory, or ability to concentrate.

A sleep specialist can help identify the underlying cause and recommend treatments, such as light therapy, melatonin supplements, or behavioral changes. Early intervention can help realign your internal clock and restore healthier sleep patterns.

Still have questions? Ask our community!

Join our Sleep Care Community — a trusted hub of sleep health professionals, product specialists, and people just like you. Whether you need expert sleep advice for your insomnia or you’re searching for the perfect mattress, we’ve got you covered. Get personalized guidance from the experts who know sleep best.

References

8 Sources

-

Reddy, S., Reddy, V., & Sharma, S. (2023, May 1). Physiology, Circadian Rhythm. StatPearls.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519507/ -

Goldstein, C. (2024 February). Overview of circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders. In R. Benca & A. Eichler (Ed.). UpToDate.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-circadian-rhythm-sleep-wake-disorders -

Wright, K. P., Jr, Hull, J. T., & Czeisler, C. A. (2002). Relationship between alertness, performance, and body temperature in humans. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology, 283(6), R1370–R1377.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12388468/ -

Cheng, P. (2024 February). Sleep-wake disturbances in shift workers. In C. Goldstein & A. Eichler (Ed.). UpToDate.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/sleep-wake-disturbances-in-shift-workers -

Goldstein, C. (2024 February). Jet lag. In R. Benca & A. Eichler (Ed.). UpToDate.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/jet-lag -

Monk T. H. (2010). Enhancing circadian zeitgebers. Sleep, 33(4), 421–422.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20394309 -

Morf, J., & Schibler, U. (2013). Body temperature cycles: gatekeepers of circadian clocks. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex.), 12(4), 539–540.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23343768/ -

Fung, C. H., Vitiello, M. V., Alessi, C. A., Kuchel, G. A., & AGS/NIA Sleep Conference Planning Committee and Faculty (2016). Report and Research Agenda of the American Geriatrics Society and National Institute on Aging Bedside-to-Bench Conference on Sleep, Circadian Rhythms, and Aging: New Avenues for Improving Brain Health, Physical Health, and Functioning. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64(12), e238–e247.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27858974/