Bruxism: Teeth Grinding at Night

- Bruxism involves teeth grinding and jaw clenching during sleep.

- Stress is the most common cause, but correlations have been found between bruxism and obstructive sleep apnea.

- Night guards can help prevent dental issues and chronic pain.

Teeth clenching and grinding are common involuntary reactions to anger, fear, or stress. In some people, this reaction plays out repeatedly through the day, even if they are not responding to an immediate stressor. This involuntary teeth grinding is known as bruxism.

Bruxism can happen while awake or asleep, but people are much less likely to know that they grind their teeth when sleeping. Because of the force applied during episodes of sleep bruxism, the condition can pose serious risks to tooth and jaw health and may require treatment to reduce its impact.

Is Your Troubled Sleep a Health Risk?

A variety of issues can cause problems sleeping. Answer three questions to understand if it’s a concern you should worry about.

What Is Sleep Bruxism?

Sleep bruxism is teeth grinding that happens during sleep, and is marked by movement of the masticatory muscles responsible for chewing. Sleep bruxism and waking bruxism are considered to be distinct conditions , even though the physical action is similar. Of the two, awake bruxism is more common.

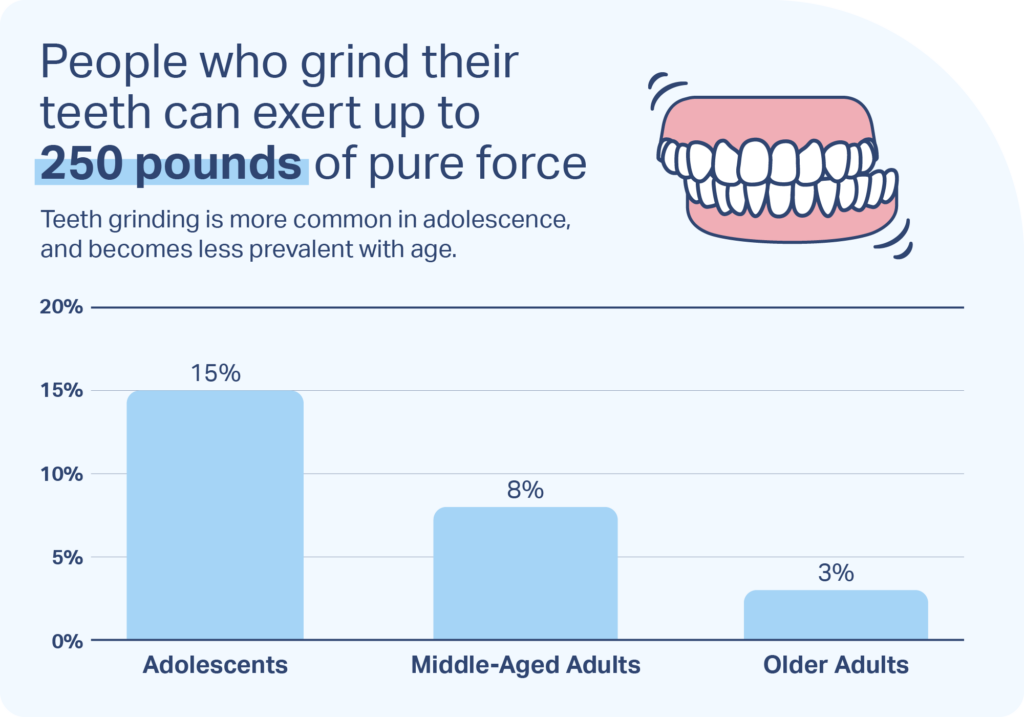

It is often much harder for people to be aware that they are grinding their teeth while sleeping, which makes diagnosis challenging. A sleeping person cannot perceive their bite strength, so they may clench more tightly and grind their teeth, employing up to 250 pounds of force .

How Common Is Sleep Bruxism?

Sleep bruxism is more common in children, adolescents, and young adults than middle-aged and older adults. Exact numbers of how many people have sleep bruxism are hard to come by because many people are not aware that they grind their teeth at night.

Statistics about sleep bruxism in children are the hardest to pin down. Studies have found anywhere from around 6% to up to nearly 50% of children experience nighttime teeth grinding. It can affect children as soon as teeth come in, so some infants and toddlers may grind their teeth. Some sleep disorders , including sleep talking, sleepwalking, and bedwetting, are believed to increase risk of sleep bruxism in children.

In adolescents, the prevalence of sleep bruxism is estimated to be around 15% . The condition becomes less common with age, as around 8% of middle-aged adults and only 3% of older adults are believed to grind their teeth during sleep.

What Are the Symptoms of Sleep Bruxism?

The main symptom of sleep bruxism is involuntary clenching and grinding of the teeth during sleep. People with sleep bruxism don’t grind their teeth throughout the night, but have episodes of clenching and grinding which usually last up to one second. The frequency of episodes is often inconsistent, and teeth grinding may not occur every night.

Some amount of mouth movement is normal during sleep. Up to 60% of people make occasional chewing-like motions known as rhythmic masticatory muscle activities (RMMA), but in people with sleep bruxism, these occur with greater frequency and force.

It is normal for people who grind their teeth at night to not be cognizant of this behavior unless they are told about it by a family member or bed partner. However, some symptoms, like jaw and neck pain, can be an indication of sleep bruxism.

The majority of sleep bruxism takes place early in the sleep cycle, during stages 1 and 2 of non-REM sleep, but the pain and discomfort may only be noticed after waking up. Pain occurs due to the tightening of jaw muscles during episodes of bruxism. Morning headaches that feel like tension headaches and unexplained damage to teeth can also be a sign of nighttime clenching and grinding of teeth.

What Are the Consequences of Sleep Bruxism?

Long-term consequences of sleep bruxism can include significant harm to the teeth . Teeth may become painful, eroded, and mobile. Dental crowns, fillings, and implants can also become damaged.

Teeth grinding can increase the risk of problems with the joint that connects the lower jaw to the skull, known as the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). TMJ issues can provoke difficulty chewing, chronic jaw pain, popping or clicking noises, locking of the jaw, and other complications.

Not everyone with sleep bruxism will have serious effects. The extent of symptoms and long-term consequences depend on the severity of the grinding, the alignment of a person’s teeth, their diet, and whether they have other conditions that can affect the teeth like gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Why Do I Grind My Teeth at Night?

Multiple factors influence the risk of sleep bruxism, so it can be difficult to identify a single cause for why people grind their teeth. That said, certain risk factors are associated with a greater probability of sleep bruxism.

- High stress levels: Stress is one of the most significant risk factors. Clenching the teeth when facing negative situations is a common reaction, which can carry over to episodes of sleep bruxism. Teeth grinding is also believed to be connected to higher levels of anxiety.

- Genetics: Researchers have determined that sleep bruxism has a genetic component and can run in families. As many as half of people with sleep bruxism will have a close family member who also experiences the condition.

- Irregular sleep patterns: Episodes of teeth grinding appear to be connected to changing sleep patterns or microarousals from sleep. Most teeth grinding is preceded by increases in brain and cardiovascular activity. This may explain the associations that have been found between sleep bruxism and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which causes temporary sleep interruptions from lapses in breathing.

- Lifestyle: Numerous other factors have been associated with sleep bruxism including cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, caffeine intake, depression, and snoring. Further research is needed to better understand potential connections and how these factors may affect sleep bruxism.

- Medications: Research suggests certain medications, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), amphetamines, and antipsychotics may increase risk of sleep bruxism. It is important to discuss dosage and potential side effects of any medications with your doctor.

How Is Sleep Bruxism Diagnosed?

Sleep bruxism is diagnosed by a doctor or a dentist , but the diagnostic process can vary depending on the type of health professional providing care.

An overnight study in a sleep clinic, known as polysomnography, is the most conclusive way to diagnose sleep bruxism. However, polysomnography can be time-consuming and expensive and may not be necessary in certain cases. Polysomnography can identify other sleep problems, like OSA, so it may be especially useful when a person has diverse sleep complaints.

Home observation tests can monitor for signs of teeth grinding, but these tests are considered to be less definitive than polysomnography.

What Are the Treatments for Sleep Bruxism?

There is no treatment that can completely eliminate or cure teeth grinding during sleep, but several approaches can decrease episodes and limit damage to the teeth and jaw.

The best treatment for sleep bruxism varies based on the individual, and should always be overseen by a doctor or dentist who can explain the benefits and downsides of a therapy in the patient’s specific situation.

Stress Reduction

Taking steps to reduce and manage stress may help naturally decrease teeth grinding. Reducing exposure to stressful situations is ideal, but of course, it is impossible to completely eliminate stress. As a result, many approaches focus on combating negative responses to stress in order to reduce its impact.

Techniques for reframing negative thoughts are a component of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), a form of talk therapy for improving sleep that may address anxiety and stress as well. Improving sleep hygiene and employing relaxation techniques can have added benefits for falling asleep more easily.

Medications

Medications help some people reduce sleep bruxism. Most of these drugs work by altering brain chemicals to reduce muscle activity involved in teeth grinding. Botox injections are another way of limiting muscle movement and have shown effectiveness in more severe cases of sleep bruxism.

Medications may have side effects that make them unsuitable for some patients or difficult to use long-term. It is important to speak with a doctor before taking any medication for sleep bruxism in order to best understand its potential benefits and side effects.

Mouthpieces

Various types of mouthpieces and mouthguards, sometimes called night guards, are used to reduce damage to the teeth and mouth that can occur because of sleep bruxism.

Dental splints can cover the teeth so that there is a barrier against the harmful impact of grinding. Splints are often specially designed by a dentist for the patient’s mouth but are also sold over-the-counter. They may cover just a section of teeth or cover a wider area, such as the whole upper or lower rows of teeth.

Other types of splints and mouthpieces, including mandibular advancement devices (MADs), work to stabilize the mouth and jaw in a specific position and prevent clenching and grinding. MADs work by holding the lower jaw forward, and they are commonly used to reduce chronic snoring .

Symptom Relief

Avoiding gum and hard foods can cut down on painful movements of the jaw. A hot compress or ice pack applied to the jaw may provide temporary pain relief.

Facial exercises help some people reduce the pain in their jaw or neck. Facial relaxation and massage of the head and neck area may further reduce muscle tension. A doctor or dentist may be able to suggest specific exercises or make a referral to an experienced physical therapist or massage therapist.

Still have questions? Ask our community!

Join our Sleep Care Community — a trusted hub of sleep health professionals, product specialists, and people just like you. Whether you need expert sleep advice for your insomnia or you’re searching for the perfect mattress, we’ve got you covered. Get personalized guidance from the experts who know sleep best.

Medical Disclaimer: The content on this page should not be taken as medical advice or used as a recommendation for any specific treatment or medication. Always consult your doctor before taking a new medication or changing your current treatment.

References

12 Sources

-

Yap, A. U., & Chua, A. P. (2016). Sleep bruxism: Current knowledge and contemporary management. Journal of Conservative Dentistry, 19(5), 383–389.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27656052/ -

Hennessy, B.J. (2022, February). Teeth grinding. Merck Manual Consumer Version.

https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/mouth-and-dental-disorders/symptoms-of-oral-and-dental-disorders/teeth-grinding -

Machado E., Dal-Fabbro C., Cunali P. A., Kaizer O. B. (2014). Prevalence of sleep bruxism in children: A systematic review. Dental Press Journal of Orthodontics.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25628080/ -

Gerstner, G. E. (2022, February 3). Sleep-related bruxism (tooth grinding). In A. F. Eichler (Ed.). UpToDate.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/sleep-related-bruxism-tooth-grinding -

Prado I.M., Abreu L.G., Silveira K.S., Auad S.M., Paiva S.M., Manfredini D., Serra-Negra J.M. (2018). Study of associated factors with probable sleep bruxism among adolescents. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 14(8), 1369-1376.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30092895/ -

Hennessy, B.J. (2022, February). Bruxism. Merck Manual Consumer Version.

https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/dental-disorders/symptoms-of-dental-and-oral-disorders/bruxism -

MedlinePlus: National Library of Medicine (US). (2022, January 24). TMJ disorders.

https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001227.htm -

Wieckiewicz M., Paradowska-Stolarz A., Wieckiewicz W. (2014). Psychosocial aspects of bruxism: The most paramount factor influencing teeth grinding. BioMed Research International.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25101282/ -

Martynowicz, H., Gac, P., Brzecka, A., Poreba, R., Wojakowska, A., Mazur, G., Smardz, J., & Wieckiewicz, M. (2019). The Relationship between Sleep Bruxism and Obstructive Sleep Apnea Based on Polysomnographic Findings. Journal of clinical medicine, 8(10), 1653.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31614526/ -

Ohayon M.M., Li K.K., Guilleminault C. (2001) Risk factors for sleep bruxism in the general population. Chest, 119(1), 53-61.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11157584/ -

Herrero Babiloni A., Lavigne G.J. (2018). Sleep bruxism: A “bridge” between dental and sleep medicine. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 14(8), 1281-1283.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30092910/ -

Schwab, R. J. (2022, May). Snoring. Merck Manual Professional Version.

https://www.merckmanuals.com/en-pr/professional/neurologic-disorders/sleep-and-wakefulness-disorders/snoring