Sleep Inequity Takes Center Stage in SIDS Recommendations

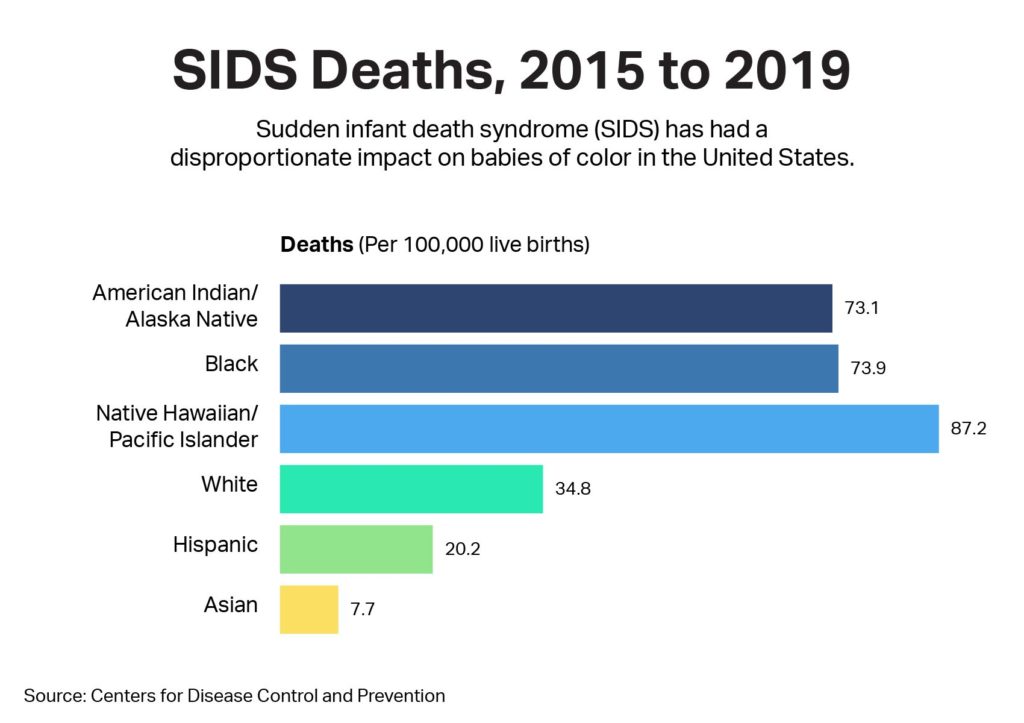

In June 2022, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) revised its long-standing Safe Sleep recommendations with a specific goal: address inequities to reduce sudden unexpected infant death (SUID) and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) among Black, American Indian, and Alaska Native babies.

Building off the academy’s call earlier in 2022 for removing race-based medicine, these revisions outline differences that may exist because of structural racism, poverty, cultural norms, and other factors. The recommendations, updated for the first time since 2016, are designed to help pediatricians discuss sleep safety with all parents and caregivers.

SIDS deaths have declined more than 60% since the academy’s Safe to Sleep campaign began in 1994. But SIDS remains a leading cause of death in infants younger than 1 year old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

More than twice as many of these SIDS deaths occur among non-Hispanic Black, American Indian, and Alaska Native babies per 100,000 live births than non-Hispanic white babies. The new AAP guidelines address reasons for this disparity head on, including unsafe sleep practices such as infants sharing beds with parents and use of soft bedding.

“This is what we’ve always striven to do, [so] we’re now taking what was always implied,” says Dr. Ben Hoffman, professor of pediatrics at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, Oregon, and chairman of the American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Injury, Violence and Poison Prevention. “If we don’t call out the disparity in SIDS deaths, and we don’t specifically talk about it, then it will continue to hide in the shadows.”

Looking at Why We Share a Bed With Our Babies

The first adjustment to the AAP recommendations addresses sharing a bed with an infant. On one hand, research shows it significantly increases the risk of SIDS. But as the latest recommendations state: “Many parents choose to routinely bed share for a variety of reasons, including facilitation of breastfeeding, cultural preferences, and belief that it is better and safer for their infant.” These could include keeping sleeping babies close in neighborhoods where crime or similar hazards are a concern. The practice also could be tradition.

According to 2018 research, bed-sharing is most prevalent among American Indians, Alaska Natives, Blacks, and Asians/Pacific Islanders, compared with whites and non-white Hispanics.

If we don't call out the disparity in SIDS deaths and we don't specifically talk about it, then it will continue to hide in the shadows. — Dr. Ben Hoffman, professor of pediatrics at Oregon Health & Science University and chairman of the American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Injury, Violence and Poison Prevention

The AAP advises that babies should be placed in their own safe space near the bed of a parent, parents, or caregiver. Babies may be brought to the parents’ bed for a short time for feeding and comfort but should always be returned to their separate space when the parent is ready to go back to sleep.

“It is important to remind mothers that they are likely going to fall asleep if they are feeding the baby in bed,” says Dr. Fern Hauck, a member of the AAP’s task force on SIDS and professor of family medicine at the University of Virginia School of Medicine. “So planning ahead is an important strategy.”

The AAP also notes that bed-sharing is not always the same as co-sleeping, which can refer to sleeping in the same room as a child.

Detailing Safe Sleep Surfaces

The 2016 recommendations simply advised to use a “firm” sleep surface. The 2022 revisions go much deeper, instructing caregivers against placing babies to sleep on any soft surfaces and offering guidance for safe options that meet federal standards.

They also acknowledge that even those options may be out of reach for some parents and caregivers.

“The reality is, many hospitals are giving out baby boxes because there’s nothing else [available],” says Alison Jacobson, executive director of First Candle, a nonprofit working to eliminate SIDS. “A baby box with nothing else [is safer than a] crib [with] blankets and pillows.”

SIDS deaths have declined more than 60% since the American Academy of Pediatrics' Safe to Sleep campaign began in 1994.

The recommendations for the first time acknowledge cradleboards, which some American Indian and Alaska Native families traditionally have used. Although researchers haven’t studied their safety, they are considered safe if babies aren’t over-bundled in clothing or coverings before being secured in place.

How to Account For Cultural Differences

For the first time, the 2022 guidelines explicitly state that pediatricians be “culturally appropriate, respectful, and nonjudgmental” when discussing sleep. The intent is to start a dialogue between doctors and parents to adopt safer sleep practices, such as breastfeeding and putting babies on their backs to sleep. Parents may be more likely to listen or share information if they feel that their opinions are valid and that they’re part of the solution.

Part of this includes a recommendation for physicians to have interpreters available when needed, as well as calling out “socioculturally appropriate intervention methods.”

Also new to the guidelines is a callout for social determinants of health, which may affect sleep safety.

“This change is important to note so that health-care providers may … take into account what other struggles the family may be impacted with that would potentially prevent them from following the new guidelines,” says Dr. Nilong Vyas, a pediatrician in New Orleans and a SleepFoundation.org board member.

Research has shown that poverty, unemployment, homelessness, and domestic violence may influence parents’ decisions to share beds or place babies on their stomachs. These factors may increase SIDS risks.

Following through on the recommendations may take time. But Dr. Hauck says adding this context can help physicians and health-care providers look beyond the recommendations themselves.

“It will allow the health-care providers to stop ‘blaming’ the parents and to be more compassionate while also opening the door to recommend resources to the families and engage others, such as social workers, to help,” she says.

References

7 Sources

-

Moon, R. Y., Carlin, R. F., Hand, I., TASK FORCE ON SUDDEN INFANT DEATH SYNDROME AND THE COMMITTEE ON FETUS AND NEWBORN, Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, Abu Jawdeh, E. G., Colvin, J., Goodstein, M. H., Hauck, F. R., Hwang, S. S., Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Cummings, J., Aucott, S., Guillory, C., Hudak, M., Kaufman, D., Martin, C., Pramanik, A., Puopolo, K., Consultants to Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, … Couto, J. (2022). Sleep-Related Infant Deaths: Updated 2022 Recommendations for Reducing Infant Deaths in the Sleep Environment. Pediatrics, e2022057990. Advance online publication., Updated 2022 Recommendations for Reducing Infant Deaths in the Sleep Environment. Pediatrics, e2022057990. Advance online publication.

https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/150/1/e2022057990/188304/Sleep-Related-Infant-Deaths-Updated-2022 -

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infant mortality. (September 16, 2024)., Retrieved July 8, 2022.

https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-infant-health/infant-mortality/index.html -

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, June 15). Data and Statistics for SIDS and SUID | CDC.

https://www.cdc.gov/sudden-infant-death/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/sids/about/index.htm -

Moon, R. Y., Carlin, R. F., Hand, I., & TASK FORCE ON SUDDEN INFANT DEATH SYNDROME. (2022). Evidence Base for 2022 Updated Recommendations for a Safe Infant Sleeping Environment to Reduce the Risk of Sleep-Related Infant Deaths. Pediatrics, 150(1)., Updated Recommendations for a Safe Infant Sleeping Environment to Reduce the Risk of Sleep-Related Infant Deaths. Pediatrics, 150(1).

https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/150/1/e2022057991/188305/Evidence-Base-for-2022-Updated-Recommendations-for -

Adams, S. M., Ward, C. E., & Garcia, K. L. (2015). Sudden infant death syndrome. American family physician, 91(11), 778–783.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26034855/ -

Bombard, J. M., Kortsmit, K., Warner, L., Shapiro-Mendoza, C. K., Cox, S., Kroelinger, C. D., Parks, S. E., Dee, D. L., D’Angelo, D. V., Smith, R. A., Burley, K., Morrow, B., Olson, C. K., Shulman, H. B., Harrison, L., Cottengim, C., & Barfield, W. D. (2018). Vital Signs: Trends and Disparities in Infant Safe Sleep Practices – United States, 2009-2015. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 67(1), 39–46.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5769799/ -

Shipstone RA, Young J, Kearney L, Thompson JMD. Applying a Social Exclusion Framework to Explore the Relationship Between Sudden Unexpected Deaths in Infancy (SUDI) and Social Vulnerability. Front Public Health. 2020 Oct 20;8:563573. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.563573. PMID: 33194965; PMCID: PMC7606531.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7606531/