Parasomnias

If you’ve ever talked in your sleep, sleepwalked, or woken up with your heart racing after a frightening dream, you’ve experienced a parasomnia. Parasomnias are undesirable experiences that happen while a person is sleeping, falling asleep, or waking up . Most people experience parasomnias at some point in life.

In most cases, parasomnias are not harmful. But, they may be disturbing or frustrating. In some cases, parasomnia activity can be dangerous to sleepers or their bed partners, or a symptom of an underlying medical condition.

Looking to improve your sleep? Try upgrading your mattress.

What Causes Parasomnias?

Not all parasomnias have a clear cause, but researchers have identified several potential causes and triggers for parasomnias.

- Sleep deprivation: If you don’t get enough sleep, you’re more likely to experience parasomnias . This may be because sleep deprivation can alter the stages of sleep .

- Disturbed sleep: Frequent nighttime sleep disruptions can provoke parasomnias. If you have a condition that disturbs sleep, such as sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, or chronic pain, you may be more vulnerable to parasomnias.

- Stress: If you are feeling stress or anxiety, or if a negative life event has recently affected you, you may experience parasomnias .

- Psychological disorders: Research has linked depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and other mental health conditions to parasomnias.

- Neurological disorders and diseases: Conditions that affect the nervous system can cause parasomnias. These include narcolepsy, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, dementia, brain tumors, and more.

- Medications: Some medications may make parasomnias more likely, including certain antidepressants.

- Inherited traits: Genes play a role in some parasomnias, so if you have a family history of a certain parasomnia, you may be more likely to experience them.

Parasomnias and the Sleep Cycle

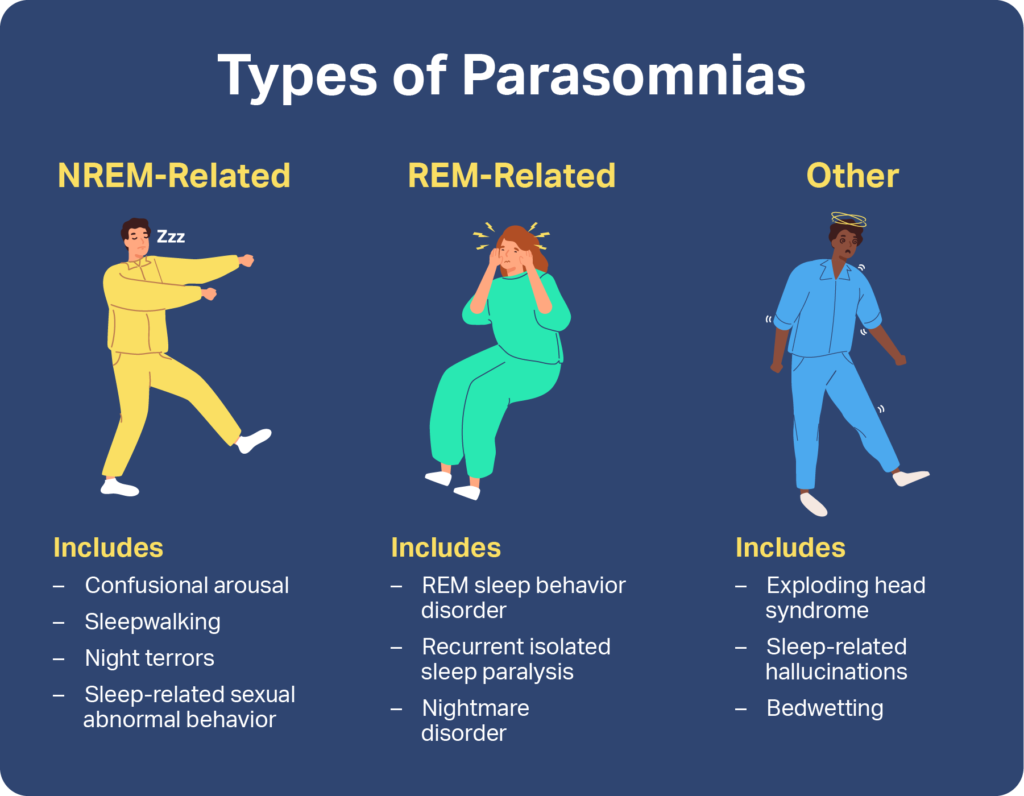

Sleep experts classify parasomnias by the stages of sleep they occur during. Some are associated with non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, which encompasses the first three stages of sleep, while others happen during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. Other parasomnias may occur during any sleep stage or during the transition into or out of wakefulness.

NREM-Related Parasomnias

The parasomnias that happen during NREM sleep are often described as “disorders of arousal.” People who experience them partially wake up. Their eyes may be open, and they may appear to act with intention. However, they may not respond when spoken to, and they may have no memory of what happened afterward . NREM-related parasomnias tend to be more common in children .

REM-Related Parasomnias

REM-related parasomnias occur during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep or in the transition out of it. These parasomnias tend to occur in the final hours of a night’s sleep, often very early in the morning. Unlike non-REM parasomnias, individuals can usually remember these episodes.

Other Parasomnias

Some parasomnias are not associated with NREM or REM sleep, because they can happen at any time during sleep or they happen when a person is falling asleep or waking up. Sleep experts classify these behaviors and events as “other parasomnias.”

How Are Parasomnias Treated?

Treatment for parasomnias can vary depending on the type of parasomnia and its cause. Some parasomnias require no treatment, while doctors may recommend managing others with:

- Healthy sleep habits

- Stopping or stopping certain medications

- Therapy

- Relaxation techniques

If you or someone in your care is experiencing parasomnias, talk to a doctor. A medical professional can help you manage symptoms, improve sleep, and stay safe throughout the night.

Still have questions? Ask our community!

Join our Sleep Care Community — a trusted hub of sleep health professionals, product specialists, and people just like you. Whether you need expert sleep advice for your insomnia or you’re searching for the perfect mattress, we’ve got you covered. Get personalized guidance from the experts who know sleep best.

References

7 Sources

-

Alshahrani, S. M., Albrahim, R. A., Abukhlaled, J. K., Aloufi, L. H., & Aldharman, S. S. (2023). Parasomnias and associated factors among university students: A cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia. Cureus, 15(11), e48722.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38094542 -

Singh, S., Kaur, H., Singh, S., & Khawaja, I. (2018). Parasomnias: A comprehensive review. Cureus, 10(12), e3807.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30868021/ -

Kirsch, D. (2023, July 25). Stages and architecture of normal sleep. UpToDate.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/stages-and-architecture-of-normal-sleep -

Vaughn, B. V. (2024, June 11). Approach to abnormal movements and behaviors during sleep. UpToDate.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-abnormal-movements-and-behaviors-during-sleep -

Zak, R., & Karippot, A. (2023, October 18). Nightmares and nightmare disorder in adults. UpToDate.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/nightmares-and-nightmare-disorder-in-adults -

A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. (2023, April 28). Night terrors in children. MedlinePlus.

https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000809.htm -

Mainieri, G., Loddo, G., & Provini, F. (2021). Disorders of arousal: A chronobiological perspective. Clocks & Sleep, 3(1), 53–65.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33494408/