When you buy through our links, we may earn a commission. Products or services may be offered by an affiliated entity. Learn more.

Sleep Paralysis

- Sleep paralysis is a temporary inability to move or speak that occurs directly after falling asleep or waking up.

- Individuals maintain consciousness during episodes, which frequently involve hallucinations or a sensation of suffocation.

- No one knows exactly what causes sleep paralysis, but it is linked to sleep disorders and certain mental health conditions.

Imagine waking up and being completely aware of your surroundings but unable to move. It might feel like a dream, a nightmare, or something in between. This eerie experience is known as sleep paralysis. Though often harmless, it can feel terrifying in the moment. Understanding what’s happening behind the scenes can help take the fear out of this strange sleep glitch.

What Is Sleep Paralysis?

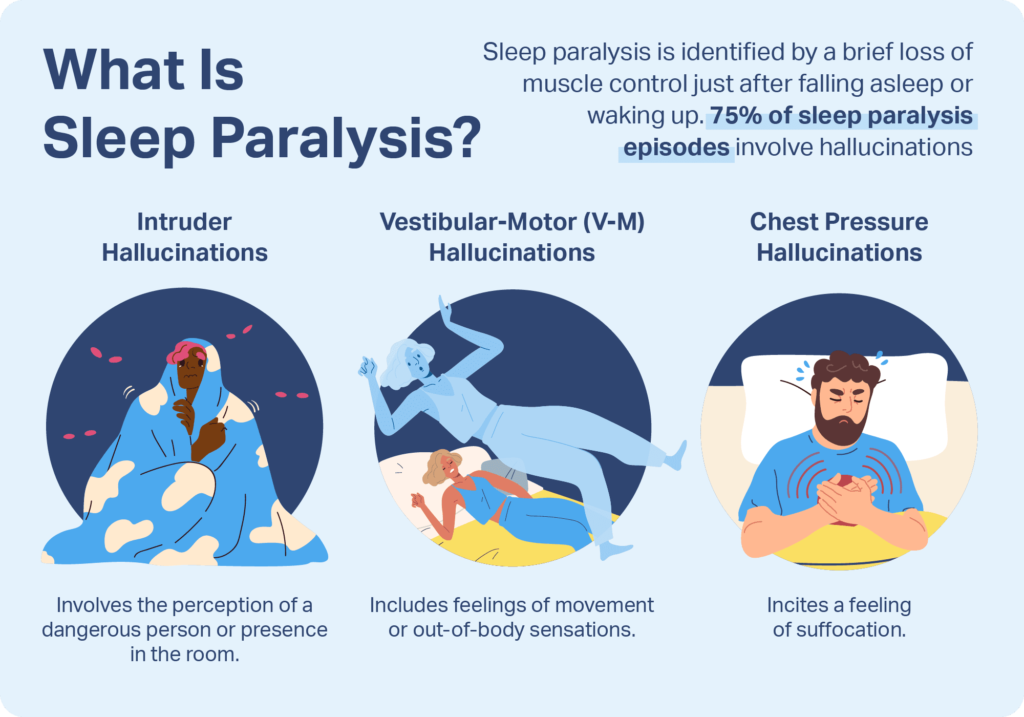

Sleep paralysis is a condition marked by a brief loss of muscle control, known as atonia , that happens just after falling asleep or before waking up. In addition to atonia, people often experience hallucinations during episodes of sleep paralysis.

Sleep paralysis is considered a parasomnia, which are abnormal behaviors during sleep. Because it’s linked to the rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, sleep paralysis is considered to be a REM parasomnia. While standard REM sleep involves vivid dreaming along with atonia, both typically end upon waking up, so a person never becomes conscious of this inability to move.

As a result, researchers believe that sleep paralysis involves a mixed state of consciousness that blends both wakefulness and REM sleep. In effect, the atonia and mental imagery of REM sleep seems to persist even into a state of being aware and awake.

Types of Sleep Paralysis

Medical experts typically group sleep paralysis cases into two categories .

- Isolated sleep paralysis: These one-off episodes are not connected to an underlying diagnosis of narcolepsy, a neurological disorder that prevents the brain from properly controlling wakefulness.

- Recurrent sleep paralysis: This condition involves multiple episodes over time. Recurrent sleep paralysis can be associated with narcolepsy.

In many cases, these two defining characteristics are combined to describe a condition called recurrent isolated sleep paralysis (RISP), which involves ongoing episodes in someone who does not have narcolepsy.

Looking to improve your sleep? Try upgrading your mattress.

What Are the Symptoms of Sleep Paralysis?

The defining symptom of sleep paralysis is atonia, or the inability to move the body or speak. People also report:

- Difficulty breathing

- Chest pressure

- Distressing emotions like panic or helplessness

- Feeling excessively sleepy or fatigued the day after

An estimated 75% of episodes also involve hallucinations that are distinct from typical dreams. These can occur as hypnagogic hallucinations when falling asleep or as hypnopompic hallucinations when waking up. These hallucinations fall into three categories.

- Intruder hallucinations: These hallucinations involve the perception of a dangerous person or presence in the room, sometimes referred to as sleep paralysis demons.

- Chest pressure hallucinations: Also called incubus hallucinations, these episodes may incite feelings of suffocation or the sensation that someone is sitting on your chest. These frequently occur in tandem with intruder hallucinations.

- Vestibular-motor (V-M) hallucinations: V-M hallucinations can include feelings of movement, such as flying, or out-of-body sensations.

Sleep paralysis symptoms typically last anywhere from a few seconds to 20 minutes, and the average length is around six minutes . In most cases, episodes end on their own but occasionally are interrupted by another person’s touch or voice, or by intense effort to move that overpowers atonia.

What Causes Sleep Paralysis?

The exact cause of sleep paralysis is unknown. Studies have analyzed data to determine what heightens one’s risk of sleep paralysis, and have found mixed results. Based on those findings, researchers believe that multiple factors are involved in the onset of sleep paralysis.

Sleep Disorders

Sleep disorders and other sleeping problems have shown some of the strongest correlations with isolated sleep paralysis. Higher rates of sleep paralysis — 38% in one study — are reported by people with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), a sleep disorder marked by repeated lapses in breathing. It’s also more common in people with chronic insomnia, circadian rhythm dysregulation and nighttime leg cramps.

Narcolepsy

A pattern of multiple episodes over a period of time may be connected to narcolepsy. Narcolepsy can alter the function of neurotransmitters in the brain, which may cause complications during REM sleep, including sleep paralysis.

While roughly 20% of the general population experiences infrequent bouts of sleep paralysis, episodes are generally more frequent in those with narcolepsy. Consider speaking with your doctor if you experience signs of narcolepsy, including episodes of falling asleep without warning at inappropriate times, excessive daytime sleepiness, or muscle weakness.

Mental Health Disorders

Certain mental health conditions have shown a connection to sleep paralysis. Some of the strongest associations are in people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and others who have been exposed to physical and emotional distress.

Those with anxiety disorders, including panic disorder, also appear to be more likely to experience the condition. Stopping alcohol or antidepressants can lead to REM rebound, which may also cause sleep paralysis. Studies have found a higher risk in people with a family history of sleep paralysis, but no specific genetic basis has been identified.

Dream Patterns

Some studies have found that people who show traits of imaginativeness and disassociation from their immediate environment, such as daydreaming, are more likely to experience sleep paralysis. There may be a link as well between sleep paralysis and vivid nightmares or lucid dreaming. Further research is necessary to investigate these correlations and better understand the numerous potential causes of sleep paralysis.

Is Sleep Paralysis Dangerous?

For most people, sleep paralysis is not considered dangerous. Though it may cause emotional distress, it is classified as a benign condition and usually does not happen frequently enough to cause significant health effects.

However, an estimated 10% of people have more recurrent or bothersome episodes that make it especially troubling. As a result, they may develop negative thoughts about going to bed, reducing time allotted for sleep or provoking anxiety around bedtime that makes it harder to get restful sleep. This resulting sleep deprivation can lead to excessive daytime sleepiness and numerous other consequences for a person’s overall health.

What Are the Treatments for Sleep Paralysis?

While sleep paralysis can feel frightening, it’s often manageable with the right approach. If you find yourself experiencing sleep paralysis, it can be helpful to focus on small, intentional movements, such as wiggling a finger or toe. Reminding yourself that the episode is temporary and not dangerous may reduce panic. Deep, steady breathing and keeping your eyes focused (if they’re open) on a fixed point can also help ease you out of paralysis more quickly.

One of the most important steps is identifying and treating any underlying issues that may be contributing to disrupted sleep. Conditions like insomnia, anxiety, depression, and narcolepsy can all increase the risk of sleep paralysis episodes. A health care provider can help diagnose these conditions and recommend appropriate treatment, which may reduce or eliminate episodes altogether.

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is another evidence-based treatmentthat may help. CBT-I works by changing unhelpful thoughts and behaviors around sleep, promoting more restful and consistent sleep patterns.

Because poor sleep habits and stress are often linked to sleep paralysis, CBT-I may indirectly reduce the frequency of episodes. Researchers are also exploring a version of CBT tailored specifically to sleep paralysis , but more studies are needed to confirm its effectiveness.

How Can You Prevent Sleep Paralysis?

Because of the connection between sleep paralysis and general sleeping problems, improving sleep hygiene is a common focus in preventing sleep paralysis. Creating a consistent, calming sleep routine can help stabilize your sleep cycle and reduce the likelihood of experiencing paralysis upon waking or falling asleep.

Here are several science-backed sleep hygiene tips:

- Establish a routine: Follow the same schedule for going to bed and waking up every day, including on weekends. A soothing pre-bed routine can help you get comfortable and relaxed.

- Optimize your sleep space: Outfit your bed with the best mattress andpillow for your needs. It is also useful to design your bedroom to have limited intrusion from light or noise.

- Curb substance use: Reduce alcohol and caffeine intake, especially in the evening.

- Remove distractions: Put away electronic devices, including smartphones, for at least an hour before bed.

- Manage stress: Daily stress management through mindfulness, journaling, therapy, or deep breathing can support more restful sleep.

- Get enough sleep: Most adults need seven to nine hours of sleep per night. Skimping on sleep or staying up too late can increase your risk of sleep disruptions, including paralysis.

Frequently Asked Questions

How common is sleep paralysis?

Prevalence varies, but researchers believe that about 20% of people experience sleep paralysis at some point in their life. There is little data among this group about how often episodes recur. Sleep paralysis can occur at any age, but first symptoms often show up in childhood, adolescence, or young adulthood. After starting during teenage years, episodes may occur more frequently in a person’s 20s and 30s.

When does sleep paralysis usually happen?

Sleep paralysis usually occurs during transitions between sleep and wakefulness—either just as you’re falling asleep (called hypnagogic sleep paralysis) or as you’re waking up (known as hypnopompic sleep paralysis). It’s most likely to happen during REM sleep, when your brain is active but your body remains temporarily paralyzed to prevent you from acting out dreams.

Who is most at risk for sleep paralysis?

Sleep paralysis can affect anyone, but certain groups are more at risk. People with irregular sleep schedules—such as shift workers or frequent travelers—are more prone to episodes, as are those who sleep on their backs.

High levels of stress, anxiety, or trauma, as well as conditions like narcolepsy or PTSD, can also increase the likelihood. Genetics may play a role, too, as sleep paralysis sometimes runs in families. Adolescents and young adults tend to report it more often, especially during times of significant life changes or disrupted sleep.

Does sleep paralysis have any meaning?

The perception of sleep paralysis episodes has been found to vary significantly based on a person’s cultural context

. About 90% of episodes are associated with fear, while only a minority have more pleasant or even blissful hallucinations.

Sleep paralysis has been interpreted differently across various spiritual and cultural beliefs. To some, it may be considered as a sign of something malevolent targeting you. To others, it may be considered a sign of spiritual awakening. Interpretations vary widely, but negative experiences during episodes have led to many stories and myths about sleep demons.

Still have questions? Ask our community!

Join our Sleep Care Community — a trusted hub of sleep health professionals, product specialists, and people just like you. Whether you need expert sleep advice for your insomnia or you’re searching for the perfect mattress, we’ve got you covered. Get personalized guidance from the experts who know sleep best.

References

11 Sources

-

Brooks, P. L., & Peever, J. H. (2008). Unraveling the mechanisms of REM sleep atonia. Nature and Science of Sleep, 10, 355-367.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19226735/ -

Zhang, W., & Guo, B. (2018). Freud’s dream interpretation: A different perspective based on the self-organization theory of dreaming. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1553.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30190698/ -

Denis, D., French, C. C., & Gregory, A. M. (2018). A systematic review of variables associated with sleep paralysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 38, 141–157.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28735779/ -

Sharpless, B. A. (2016). A clinician’s guide to recurrent isolated sleep paralysis. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 1761–1767.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27486325/ -

Hsieh, S. W., Lai, C. L., Liu, C. K., Lan, S. H., & Hsu, C. Y. (2010). Isolated sleep paralysis linked to impaired nocturnal sleep quality and health-related quality of life in Chinese-Taiwanese patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Quality of Life Research, 19(9), 1265–1272.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20577906/ -

Singh, S., Kaur, H., Singh, S., & Khawaja, I. (2018). Parasomnias: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus, 10(12), e3807.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30868021/ -

Denis, D., & Poerio, G. L. (2017). Terror and bliss? Commonalities and distinctions between sleep paralysis, lucid dreaming, and their associations with waking life experiences. Journal of Sleep Research, 26(1), 38–47.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27460633/ -

Kaczkurkin, A. N., & Foa, E. B. (2015). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: an update on the empirical evidence. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 17(3), 337–346.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26487814/ -

Denis, D., French, C. C., Schneider, M. N., & Gregory, A. M. (2018). Subjective sleep-related variables in those who have and have not experienced sleep paralysis. Journal of Sleep Research, 27(5), e12650.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29280229/ -

Scammell, T. E. (2022, July 12). Clinical features and diagnosis of narcolepsy in adults. In A. F. Eichler (Ed.). UpToDate.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-features-and-diagnosis-of-narcolepsy-in-adults# -

Olunu, E., Kimo, R., Onigbinde, E.O., Akpanobong, M.A.U., Enang, I.E., Osanakpo, M., Monday, I.T., Otohinoyi, D.A., & Fakoya A.O. (2018). Sleep paralysis, a medical condition with a diverse cultural interpretation. International Journal of Applied & Basic Medical Research, 8(3), 137–142.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30123741/